A drought-accelerated shift of the cattle industry back to the Midwest forces meatpackers to strategize for reliable supplies and sales.

Decisions,

decisions

For Cargill, there was one packing plant too many. The drought-induced liquidation of cattle in Texas and reduced imports from Mexico meant there wasn’t enough to feed both its Plainview and Friona, Texas, plants. They’re 76 miles apart, virtual next-door neighbors in the wide-open Panhandle.

“We were watching cattle producers and feeders being battered by record input costs, especially feed corn,” says John Keating, president of Cargill Beef. “Combined [with drought, the impacts of country-of-origin labeling on cattle imports from Mexico and the loss of revenue from its finely textured beef product, which got caught up in the “pink slime” PR debacle], there was somewhat of a ‘perfect storm.’ I personally know many of the people impacted at Plainview, and idling a processing plant that size is never something we wanted to do, but it was something that had to be done for the good of Cargill’s beef business."

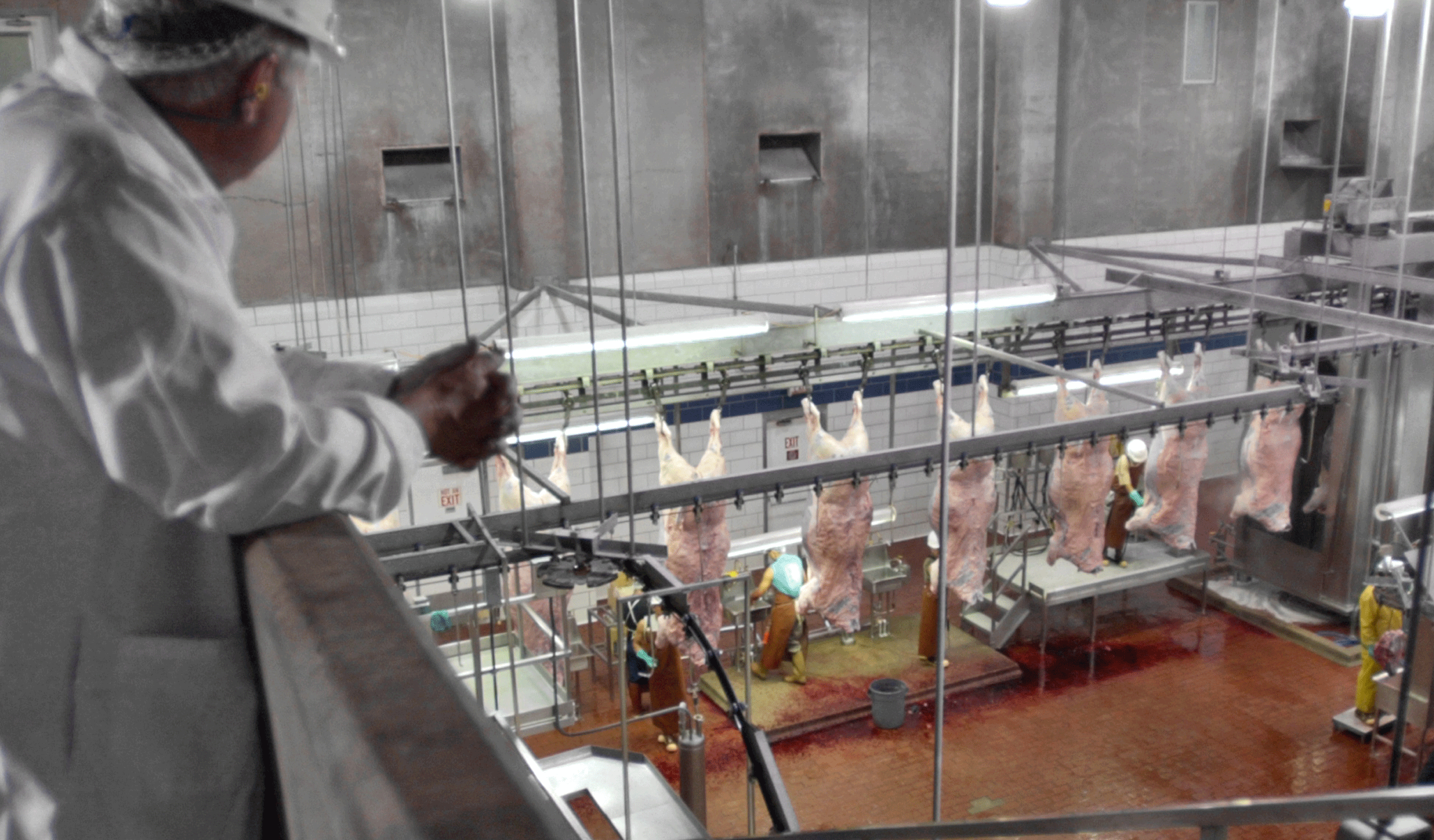

Some meatpackers are increasing production of ground beef to help retailers maintain prices at a level that is tolerable for consumers. Photo credit:

Idling the Plainview plant, which employed at least 2,000 people and slaughtered 4,500 head of cattle per day, meant Cargill could operate Dodge City, Kan., Friona and Fort Morgan, Colo., at or near capacity, providing those employees with paychecks for working a full week. “Regarding the Cargill beef processing facility in Plainview, what we said last year has not changed — we do not see the cattle supply improving for a number of years and the plant remains idle,” Keating says.

The northward tilt of cattle feeding and supply brings to bear strategic decisions by the Southern Plains packers, who are doing business in a dry land and where a key source of live animals — Mexico — is drying up too. The Texas Cattle Feeders Association expects fewer than 800,000 Mexican cattle to cross the border in 2014, close to the low end of the historic norm. Mexico has been dealing with its own drought issues and meanwhile is ramping up the self-sufficiency of its beef industry as U.S. country-of-origin labeling law has made it more expensive to process cattle from foreign countries.

Meanwhile, the growing advantage in the Northern Plains means that a packer with a plant there is potentially subsidizing any plants it might also own in the Southern Plains, and having to decide how long he can afford to do so, particularly given the costs of trucking in corn and animals from afar. Packers will go where the reliable supply is, and beyond that ultimately have to consider how best to market beef.

Decisions, decisions

Rising temperatures in the Southern Plains have caused problems, but so too have increased costs for feed. In 2007, the federal government passed legislation requiring billions of gallons of renewable fuels to be produced every year. Much of those gallons are made up of ethanol, a corn product mostly produced in the Midwest. Since 2007, the ethanol industry has siphoned away more than 40 percent of the U.S. corn crop, helping to boost prices to as high as $8 per bushel in 2008. Prices have backed off of that lofty level, but the days of cheap corn are over.

“We’ve seen long-term growth in feeder cattle in Nebraska and Iowa the last couple years. That’s really being driven by the availability of [the ethanol byproduct] dried distillers grains in those areas,” says livestock economist Steve Meyer of Paragon Economics. “That availability has given [the Midwest] a feed cost advantage that offset some of the advantages we saw in the Southwest in terms of drier conditions. I certainly think there’s a shift back to the Midwest, and the pressure on rationalization will be in the Southern Plains. There are probably too many feed yards and too many packing plants."

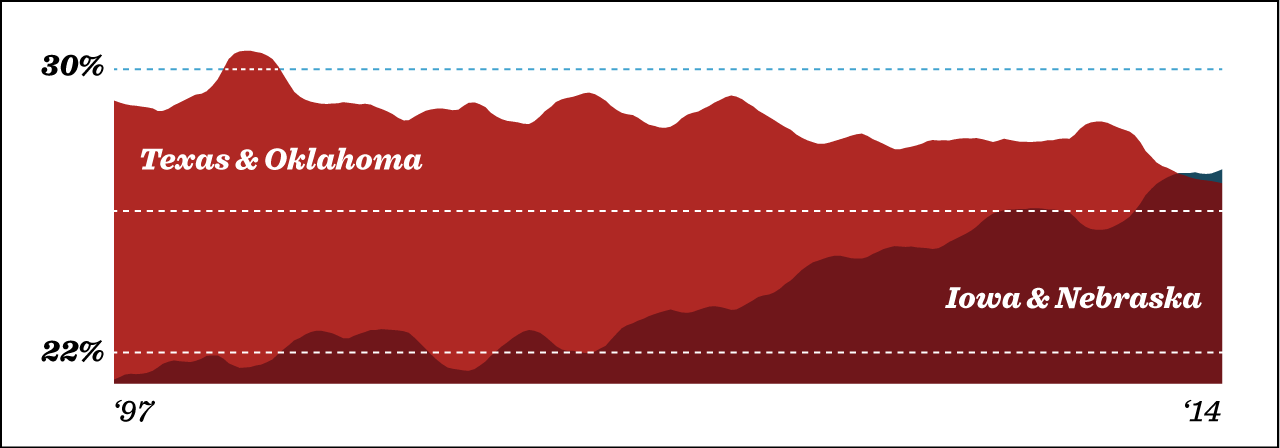

Share of U.S. cattle on feed

January 1997 to January 2014

The combined national share of cattle on feed in Nebraska and Iowa, as of January 2014, made big gains on that of Texas and Oklahoma following extreme drought in the Southern Plains. Source: Derrell Peel, Oklahoma State University/USDA

The industry’s best guess is that packing plant overcapacity is about 10 to 15 percent. John Nalivka, a livestock economist and principal of Vale, Ore.-based Sterling Marketing Inc., calculates slaughter capacity utilization at 86.5 percent, among the lowest levels in the last 22 years of his data. Feedlot overcapacity, meanwhile, is believed to be 15 to 25 percent.

Following the idling of the Plainview plant, San Angelo Packing closed in April 2013, having run out of cows to kill amid the drought. Rains in mid-May this year were encouraging, but John Sims, the company’s attorney, is realistic about the future of that facility.

“In the cow industry, if a mother cow goes down it’s just so much longer to recover,” he says. “Even if it rained today and the grass grew green, it would take two or two-and-a-half years to build a herd. You’ve got to be mindful of that all the time."

Earlier this year, National Beef’s closure of its slaughterhouse in Brawley, Calif., which slaughtered 1,900 head of cattle per day and employed 1,300 people, clouded the future for that state’s beef industry.

Brian Coehlo, president of Central Valley Meat Co. in Hanford, Calif., says sourcing cull cows is a volatile business anyway, but the drought has only made it more so. The company has been able to maintain a five-day kill of nearly 1,200 head per day, but the animals are leaner and of a lower quality, forcing changes to processing and sales strategies. Further liquidation will provide a short-term glut of cows, as producers look to rid themselves of animals they can’t feed, but Coehlo’s looking further out and expecting to have to reduce the kill as water and feed grow scarce and expensive.

“One of the things we’re watching closely is what the feed costs are going to do here in the Central Valley,” he says. “Dairy producers need feed grown locally; they can’t bring a lot in from the Midwest due to the cost. The concern is, for example, that those [farmers] growing silage corn are irrigating 100 percent on groundwater wells. Every day we’re talking to farmers with stories of wells going dry. The demand for well drillers is so high that you can’t get someone to pick up a phone to drill a new well; it’s a year-long waiting list. So you’re watering today and halfway through the crop and you’re not even sure if you will be able to harvest it.”

Back in Texas, Cargill’s Lockney feedlot that supplied the company’s Plainview slaughterhouse also is closing. It’s but one of many, with most “for sale” signs on feedlots popping up in Texas, say land brokers who handle feed lot sales. The count, as of early April, was 13 feed yards repurposed, mostly for developing high-priced heifers; 10 closed most likely permanently and about the same closed at least temporarily; four had been demolished; and two or three more were in the bidding process. Most of those are in Texas.

Reliable suppliers

In deciding where to locate their slaughterhouses, packers would do well to familiarize themselves also with the operational characteristics of cow-calf operations in various regions, which tell them the story of the reliability of supply, says Kansas State University ag economist Glynn Tonsor.

According to a March 2011 report by USDA’s Economic Research Service, called “The Diverse Structure and Organization of U.S. Beef Cow-Calf Farms,” a survey of operations in 22 states, the Northern Plains is a more efficient and more reliable source of cattle than competing regions. The telling differences, Tonsor says, include weaning weights (the more pounds, the better the genetics, the better revenue); retained ownership (beyond weaning, a signal the producer views his animals’ offspring as average or of better performance); a more defined calving season and more frequent use of technologies such as antimicrobial ionophores.

Another interesting data point is in off-farm occupations: Producers in the Southern Plains were the most likely (almost 50 percent surveyed) to have secondary occupations to beef-cow production, compared with 18 percent of Northern Plains producers, who were the least likely to do so.

And some Texas beef producers, though understanding of the need for alternative means of revenue, lament what they say is an increasing trend of their fellow cattlemen in the state to convert land for recreational use. (Think: Hunting leases for wealthy city folk who are looking for some fun.)

Says Jay O’Brien of Amarillo, Texas-based Corsino Cattle Co./JA Ranch: “There are people who mistakenly think that since their main goal is hunting that they shouldn't run cattle …. A lot of people who have bought these recreational ranches have learned that having some sort of controlled grazing is beneficial to them, but there are others that haven’t. And so that’s competing for grassland that could diminish [cattle] numbers.”

New marketing strategy

No matter where beef is produced in this country, Rabobank livestock analyst Don Close, for one, is advocating for a shift in the manner in which cattle are fed to more closely align with the U.S. consumer’s appetite for ground beef and reduce dependence on costly corn. Demand for ground beef is increasing as the market hits historic high prices, consumers’ time shrinks and their cooking skills diminish.

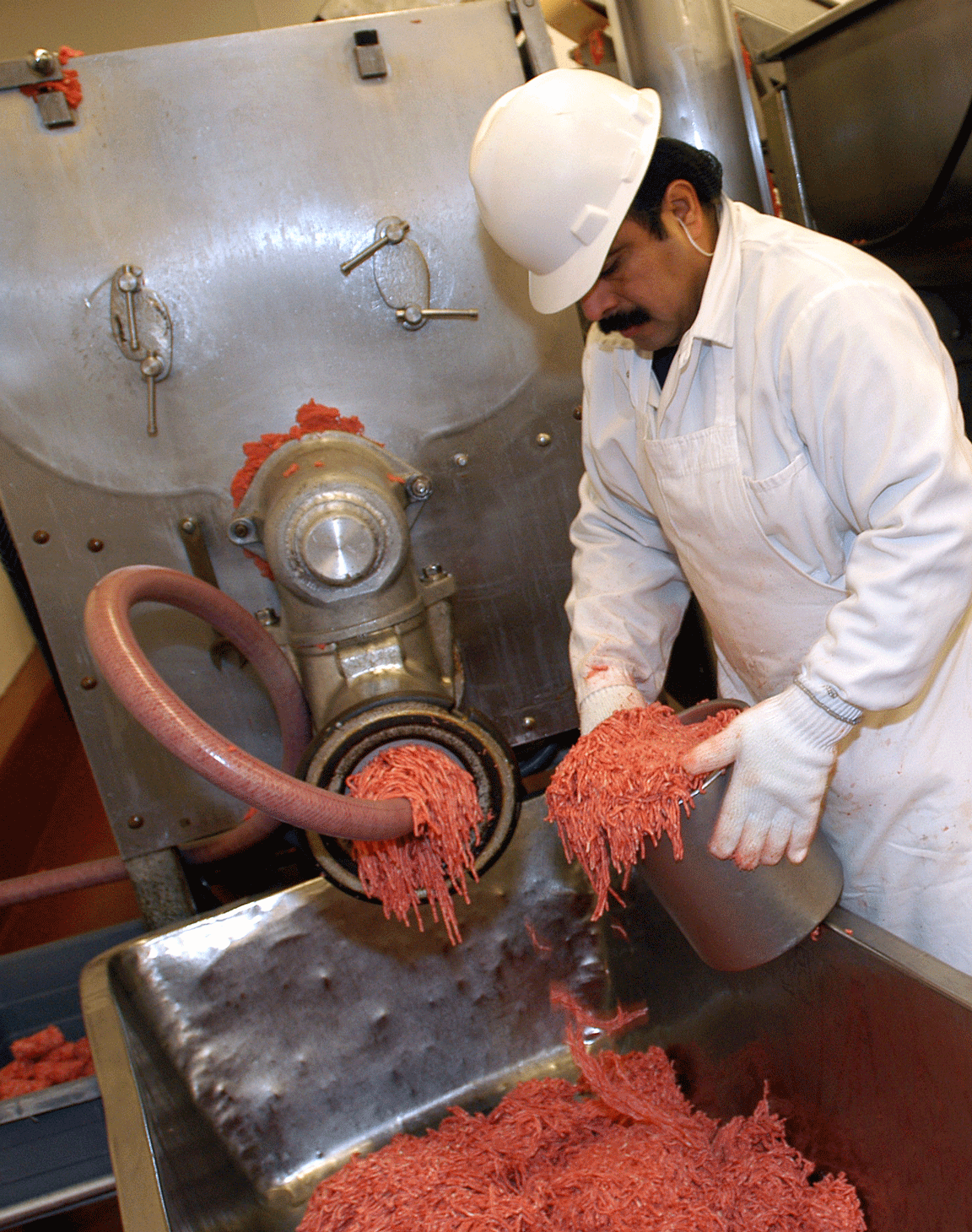

We’re producing more ground beef than we ever have.

As the industry is set up to produce high-quality middle meats, the focus is on corn-fed finishing. Close contends it’s an inefficient approach that uses too much corn and costs too much to produce animals that are a higher quality than the consumer demands. The shift would require initially the cow-calf producer to select genetics aiming for a ground beef target.

“Let’s grow those cattle bigger for a longer period of time on a low-cost ration and subsequently feed them for a shorter period of time and on a lower-cost ration,” he says. “So instead of pushing the animal to the middle to upper end of Choice grade, let’s feed for a target somewhere in the Select range. You still have versatility with the ribeye and loin component and the remainder for 80-to-85 percent lean ground beef."

Whether a permanent tweak or a temporary one, some processors’ product mixes indeed are leaning more heavily toward ground beef. In California, where a 500-year drought is squeezing supplies, Harris Ranch Beef (see more on Harris in our California case study), for example, is feeling the grind.

“It gets increasingly difficult for the retailers to maintain prices and not pass them onto consumers,” says Brad Caudill, the company’s vice president of marketing. “As prices are at an all-time high, they’re trying where they can to maintain their price structure for consumers, and it has changed some of the mix that we produce. Our ground beef business has grown exponentially over the last few months as retailers try to hold the line on prices. We’re grinding about 1 million pounds per week … . We’re producing more ground beef than we ever have.”

Ground beef is driving the value of the animal right now, making packers up their game for marketing the rest of the animal, and that will involve accessing export markets. With cow numbers down, more of the fed animal is being used for trim for grinding.

“We do need more cow meat,” says Brad Stout, manager of cattle procurement at Friona Industries’ feed yard division in Amarillo, Texas. “One of the reasons the market is moving higher [in price] is because we’re using more of the fed animal for trim. … We used to have to figure out a way to sell hamburger, because you couldn't sell the chuck and the round for enough. Now it’s a big driver."

Tyson Foods’ Emporia, Kan., plant exemplifies another type of shift that packers have to consider in the current climate. The drop in the size of the herd and excess slaughter capacity back in 2008 prompted Tyson to convert that slaughterhouse into a further processor of value-added products, such as prepared ready-to-cook meals, allowing the company to get more out of the supplies it can get its hands on.

Others aren’t so keen on Close’s idea of gearing the industry more toward ground beef, particularly given the importance of quality, highly marbled middle meats to lucrative export markets that are increasingly important to the beef industry’s profitability.

Still, industry players are at least thinking of shifting marketing strategies around shrinking cattle supplies and growing production costs.

Record-high prices

Meanwhile, those record-high wholesale and retail prices could test consumers’ willingness to pay. Wholesale beef was up 20 percent, reaching $2.44 a pound on March 18, the highest since USDA began using its current measure in 2004. The average price per pound for beef at retail reached a record $5.04 on Feb. 25, and the records continue to be broken.

You build a plant with capacity based on number of head, but every one of those head is producing more beef that has to be sold and put into the marketplace.

Meanwhile, 39 percent of U.S. consumers are eating less red meat, primarily due to higher prices, according to a study of 1,900 people by Chicago-based researcher Mintel Group Ltd. A monthly food demand survey of at least 1,000 people by Oklahoma State University showed that consumers’ willingness to pay for steak and hamburgers fell 7.58 percent and 2.40 percent in May from April. And USDA forecasts that red-meat consumption will shrink to 101.7 pounds per person this year, from 104.4 in 2013.

Years of high prices have forced the industry to take the lower-valued parts of the animal — the chucks and rounds — and develop new products that are still a cheaper buy for consumers but a higher quality as the industry has improved the carcass over time.

“We’re to a point now where we can take an item out of the chuck — for example, a flat iron or rancher’s steak — and it’s a lot better quality than it would have been 30 years ago,” says John Nalivka, a livestock economist and principal of Vale, Ore.-based Sterling Marketing. “That’s where we’re going to have to go because I don’t see any significant growth in this cattle herd.”

Given the sharp drop in both cow slaughter and heifer slaughter, Nalivka explains, the size of the U.S. cattle herd is likely beginning to stabilize and the cattle inventory will be about even with a year earlier on Jan. 1, 2015. Barring any unforeseen circumstances, by 2017, the herd will total about 91 million, a 2 percent increase from a year earlier. It will be early 2017 before any increased production will be realized, he says.

“We’re going to have to go through the painstaking exercise of finding some sort of balance between capacity and the number of livestock, and it’s not nearly as easy to do; we’re producing so much more beef per head of cattle,” Nalivka says. “You build a plant with capacity based on number of head, but every one of those head is producing more beef that has to be sold and put into the marketplace."

In the next chapter, we explore drought impacts on the California beef industry using vertically integrated Harris Ranch Beef Co. as a case study. California