Texas increasingly tells the story of a conflict that beef producers have with fellow man and nature.

Oil &

water

The cattle feeding business was originally created as a market channel for what was then a plentiful and cheap corn supply, notes Rabobank livestock analyst Don Close. It migrated to the Southern Plains in the late 1960s from the Midwest primarily because of the region’s weather advantage: milder winters and drier climate provide for longer feeding seasons. The region’s grain deficiency was offset by cheap corn prices and new feed technologies such as steam-flaked corn. Over time, the industry in Texas would come to rely heavily on imports of Mexican cattle, too, which helped temper transportation costs. Add it all up, and the state for decades has been a profitable place to raise cattle.

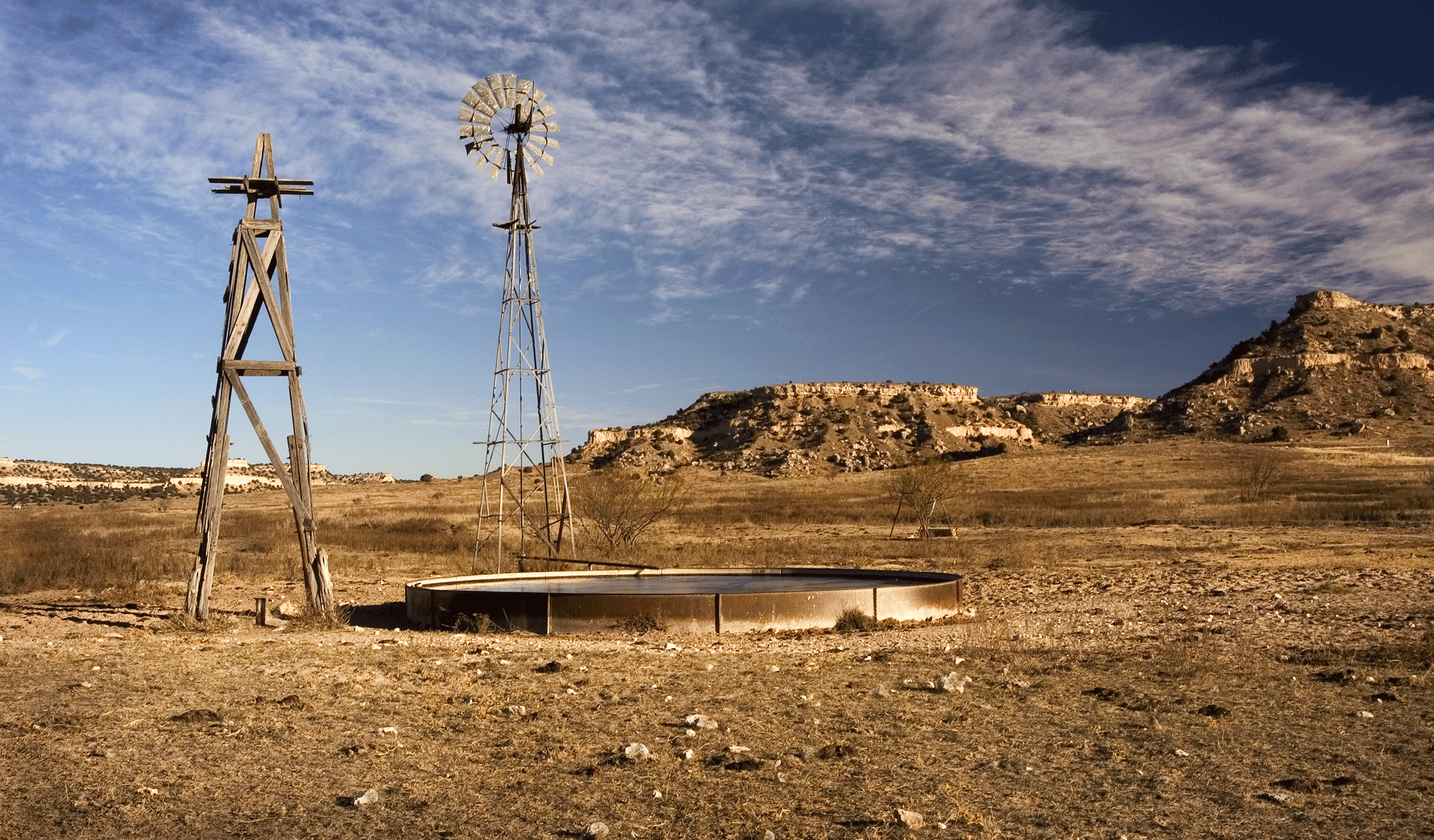

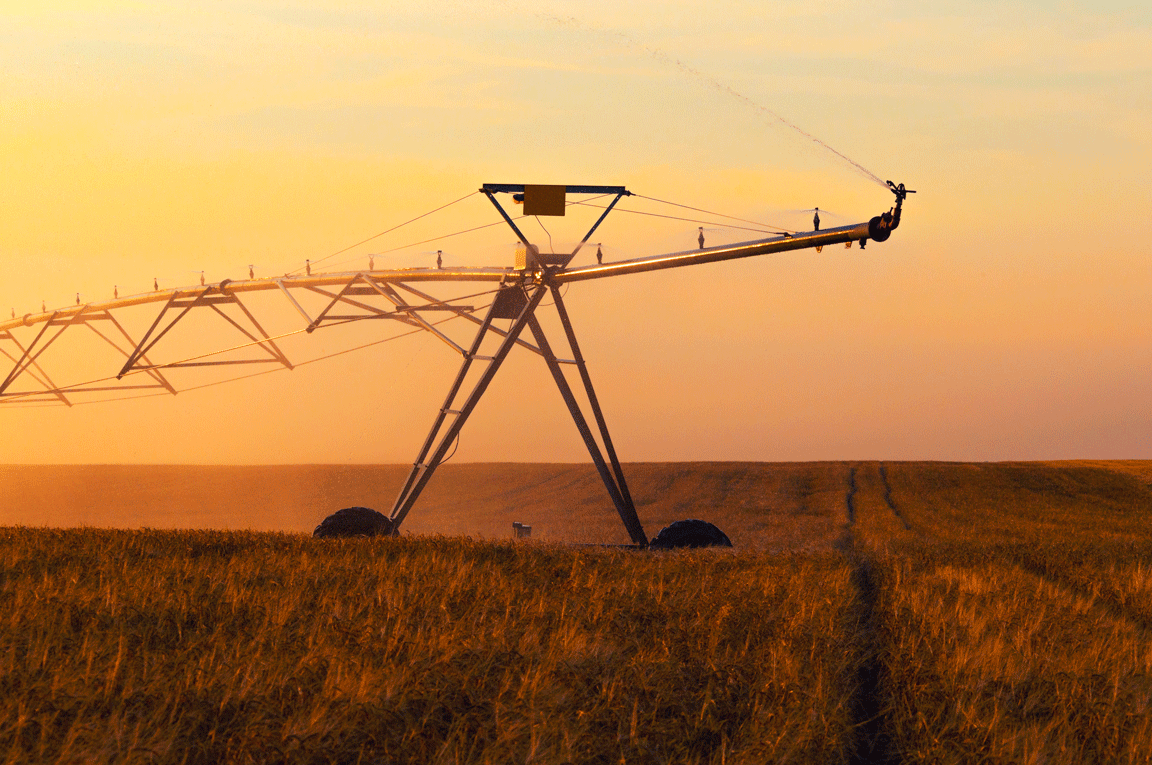

Water, flowing from a well, has become a precious commodity in drought-ravaged parts of the country including the Texas Panhandle. Photo credit:

But circumstances are changing, including the weather. Sparing the politics around global warming and its causes or even existence, climatologists will say plainly that Texas, for one, is getting hotter, according to data collected over many decades.

Average temperatures in Texas have risen by as much as 1 degree in recent decades. That may not sound like much, but Brian Fuchs, a climatologist with the National Drought Mitigation Center at the School of Natural Resources, University of Nebraska-Lincoln, says it’s a lot in the summer months. That 1 degree causes increased evaporation and use of water. After all, how widespread a drought is depends not only on precipitation but also on temperature, he says. Texas got particularly hammered in 2011, for example, due to sustained periods of heat in excess of 100 degrees, which helped to evaporate any drops of water that might have fallen.

“It’s hard to look back and say, for example, that this drought in Texas is due to climate change,” Fuchs says. “But can we attribute some of what we have seen, as far as causing the drought to intensify, to climate change? I think we can.”

A new study released this spring by the National Climate Assessment says man’s changing the climate primarily through use of fossil fuels, and that the effects of climate change already are having a negative impact on agricultural production in the United States. The study gives a region-by-region analysis and urges new management practices. In the Southern Plains, it will mean more irrigation demand.

Can we attribute some of what we have seen as far as causing the drought to intensify to climate change? I think we can.

“Expectations of more precipitation in the northern Great Plains and less in the southern Great Plains were strongly manifest in 2011, with exceptional drought and record-setting temperatures in Texas and Oklahoma — and flooding in the northern Great Plains,” the study says. “Many locations in Texas and Oklahoma experienced more than 100 days over 100°F, with both states setting new high temperature records. Rates of water loss were double the long-term average, depleting water resources and contributing to more than $10 billion in direct losses to agriculture alone. In the future, average temperatures in this region are expected to increase and will continue to contribute to the intensity of heat waves.”

One of the authors of the assessment is Texas Tech’s own Katharine Hayhoe, who did the climate projections for the study. Though married to a Texan church pastor who once scoffed at the notion of man-made climate change, Hayhoe, also a devout Christian, doesn’t see the issue as political.

“A thermometer is not a Democrat or Republican,” she says. “If we’re looking at the data, it’s not political. It is what it is.”

The data, she says, are saying that climate change is making droughts and rainfalls more extreme when they do occur.

“We’re going to get wet years again,” Hayhoe says. “But the future will be different from the past, so we need to be smarter in the ways we do things. We have to be more resilient to extremes. If we just do things the way we did in the past, we will not be successful.”

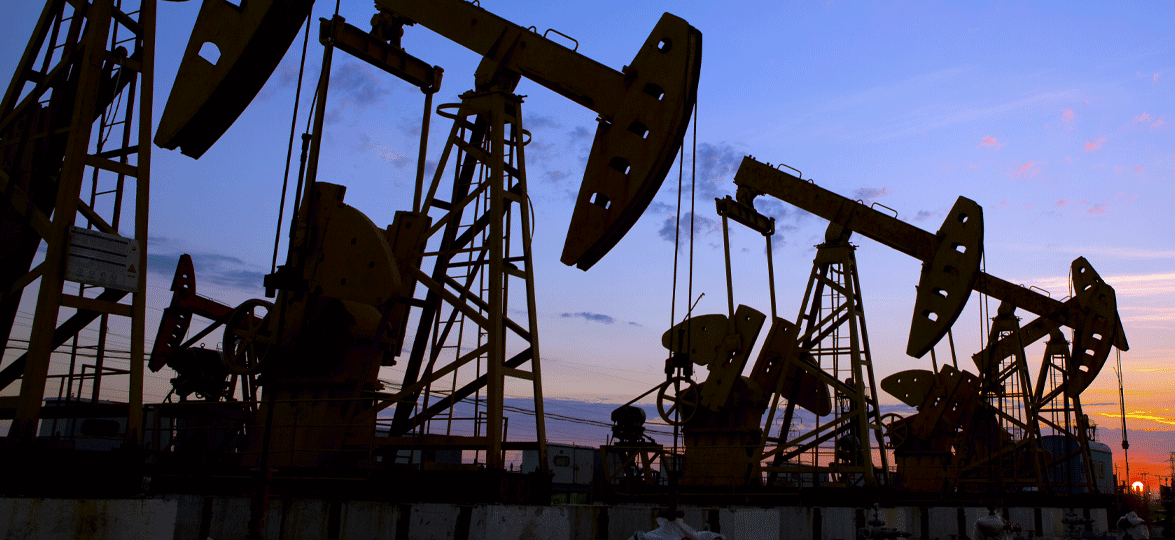

Texas tea

If there’s a more iconic commodity identified with Texas than beef, it’s oil. The state, with the advent of hydraulic fracturing (or “fracking”), is drilling deeper and, as some experts predict, could reap supplies that rival those of Saudi Arabia. A recent boom that began in 2008 with the discovery of Eagle Ford Shale in South Texas has helped rev the state’s economy: During the 24-month period from July 2009 through June of 2011, Texas created 49 percent of all new jobs created in the United States, according to Forbes. One of the perks of its oil riches is its ability to waive state income taxes, something surely not lost on the nearly 1,200 new people now moving there — per day.

A recent oil boom in Texas has boosted the economy and attracted more people to the state, whose perks include no state income taxes. Photo credit: Shutterstock

The Texas population is projected to double to more than 50 million people by 2060, and that has implications for the state’s resources and the industries that depend on them.

“When you look at the projections of surface and groundwater in the state and projected [demand], those two lines intersect pretty quickly,” says Rick Kellison, a rancher who is project manager for the Texas Tech University’s Texas Alliance for Water Conservation.

To be sure, most of the newcomers now are flocking to major cities such as Houston, Dallas and Austin. But beef interests in the Panhandle are keenly aware of the trend. They’re the ones enumerating the stats; they see the potential competition for land and particularly water.

“The Texas economy is exploding with oil and gas shales, and with land values shooting up it’s hard to justify ranching,” Trevor Caviness says, of certain parts of Texas.

In serious drought conditions, Texas does not and will not have enough water to meet the needs of its people, its businesses, and its agricultural enterprises.

Over lunch at the Hereford (Texas) Country Club in February, more browned bermuda and pickup trucks than green grass and golf carts, Trevor, his father Terry and brother Regan will allow that the drought’s most immediate impact on their business is a tighter supply of raw materials. The owners of Caviness Beef Packers have stretched outside of their normal 500-mile procurement radius, a decision that increases costs and makes for a more stressful journey for cattle, but one that also is a function of increased demand. The business is growing and, they say, they’re happy to be paying crazy prices for cattle because it’ll ensure the health of their suppliers.

At the same time, water “is our biggest long-term concern,” Terry says, facing a window that allows a view of the club’s empty swimming pool and the crumbled remains of tennis courts. Asked how the company is addressing that concern, he says, “We don’t have a 50-year plan.”

But Texas authorities are looking that far out. The State Water Plan that was published in 2012, says Texas Water Development Board spokeswoman Kimberly Leggett, was designed to emphasize facts regarding projected water demand and supply conditions and guide legislators in creating state water policy. The water plan characterizes demand as increasing by “only” 22 percent between now and 2060, but that rather conservative estimate is meant to incorporate the future role to be played by conservation, she explains. In other words, the plan doesn’t underestimate the scary nature of the issue: “In serious drought conditions, Texas does not and will not have enough water to meet the needs of its people, its businesses, and its agricultural enterprises.”

The Texas Legislature and state voters in 2013 approved the establishment of a $2 billion kitty, called the State Water Implementation Fund for Texas, that was designed to provide funding assistance to implement the recommended strategies in the State Water Plan.

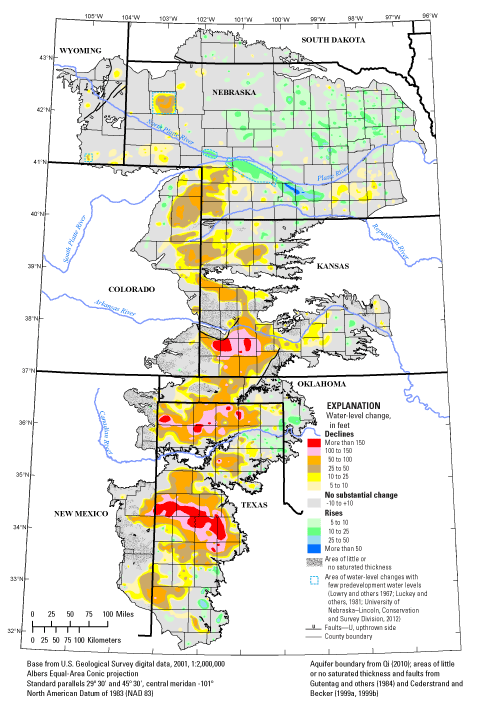

The deepest reds show the deepest draws (more than 150 feet) of water from the vast Ogallala aquifer. Agriculture interests, including cattle ranchers, rely on groundwater tapped from the aquifer. The source has been taxed particularly since 2001 as irrigation has increased. A third of the aquifer’s depletion since the 1940s occurred between 2001 and 2011. About 95 percent of the water drawn from the Ogallala in Texas is used for irrigation in the Panhandle.

Credit: US Geological Survey

Of particular concern is agriculture’s strain on the Ogallala aquifer, which underlies 35,515 square miles of Texas across 48 counties and portions of seven other states. The aquifer has been drawn down by more than 300 feet in some areas, according to the Texas Water Report that the state government completed in January. (This report provides additional emphasis to some of the more serious aspects of the State Water Plan, in part to emphasize recommended applications for funding as well as some further policy recommendations.) A third of the depletion since the 1940s occurred between 2001 and 2011. About 95 percent of the water drawn from the Ogallala in Texas is used for irrigation in the Panhandle — where, as of the end of February, only 1 percent of groundwater reservoir storage capacity was full, according to Texas Water Development Board data. Recharged primarily by rainwater, only about 1 inch of precipitation actually reaches the aquifer each year, according to the report.

Legally, Texas technically still goes by the rule of capture, whereby the owner of a well can withdraw as much water as desired even if it’s drained from beneath the land of others, although nearly 90 percent of its groundwater is managed by groundwater districts. Other Western states have abandoned rule of capture altogether for more conservative regulations. The Texas law has been the subject of numerous court cases and legislative battles since it was enacted in 1904, and more are bound to arise as the state seeks a balance of property rights and community needs, according to the Texas State Library and Archives Commission.

Trevor Caviness is an aquifer half-full kind of guy. He may have a point when he says the Ogallala will deplete to a point where farmers will be put out of business and no longer draw from it, and it will then begin to replenish.

There’s been a huge increase in demand for water, so something’s got to give — and I suppose what’s giving is agriculture, including the cattle industry.

But Texas lawmakers, voters and even ranchers aren’t exactly hip to that theory. In 2011 alone, according to the Texas Water Report, rain scarcity resulted in a 43 percent increase in water used for irrigation.

“I think with the Ogallala being a finite resource, we have insignificant recharge and the drought might have sped up its depletion,” says Kellison, whose work involves teaching fellow ranchers how to better manage their water with new technologies. His project has just received $3.6 million more in funding on top of an initial $6.2 million from various interests, including the Texas Water Board Development Council.

For example, Kellison says he is seeing a movement among ranchers away from center-pivot irrigation — the above-ground, wheeled apparatuses that create crop circles that airplane passengers see when they’re cruising high over farm land — to subsurface drip irrigation because the latter allows almost no evaporation. In growing season, such technology won’t necessarily reduce water usage but will make it more efficient, optimizing the opportunity to boost productivity with the same amount, he says.

The progress comes with a price, however. For a subsurface drip irrigation system, for example, think $1,200 to $1,600 per acre, or many millions for a large ranch.

“I don’t know of a producer not trying to do the best he can, who’s not concerned with water conservation and efficiency,” Kellison says. “But it comes down to dollars. They have to have the money to stay in business to be able to buy the equipment.”

‘Something’s got to give’

As beef packing moves toward the more temperate Midwest from Texas and other states, namely California, it might just be as nature intended, says livestock economist and Sterling Marketing principal John Nalivka. The migration to the Midwest simply entails going where more grass and water are, he says.

Cattle ranchers are moving away from center-pivot irrigation systems (shown here) to subsurface drip systems, which largely avoid evaporation caused by extreme heat. Photo credit: Shutterstock

“There’s been this huge movement of people into the western United States. Look at Phoenix,” he says. “You don’t have the resources to support the people that want to live in those areas. To me there’s been a huge increase in demand for water, so something’s got to give — and I suppose what’s giving is agriculture, including the cattle industry.”

To be fair, the northern Great Plains/Midwest region isn’t exactly ideal. A testament to the national scope of a historically low cattle herd, Cargill in July announced the closure of slaughter operations at its Milwaukee beef plant — also due to diminished cattle numbers. The region’s winters particularly showed their teeth in South Dakota in October last year when tens of thousands of cattle were killed by a freak autumn blizzard. Large Texas ranchers such as Four Sixes and Swenson Land & Cattle moved thousands of head of cattle to Nebraska in 2011 for the promise of lush grasses and plentiful water, and found it then, but the next year drought set in there, too (Nebraska’s groundwater levels in 2013 fell by 12 to 16 inches, a record decline from the previous year). Keeping their Texas real estate, meanwhile, they are building in flexibility to help withstand climatic variability.

There is no perfect climate for this business.

In the next chapter, we explore how beef ranchers approach that risk. The Ranchers