Beef ranchers in the Southern Plains are adapting to a changing climate that is testing their grit, but they remain optimistic.

West of

eden

John Perrin’s 8,000 acres in Deaf Smith Co., just shy of the New Mexico border in the Texas Panhandle, are not contiguous. It takes a while to get around, even if the dirt access roads that stretch to no end in this breathtakingly remote land allow him to drive his pickup pretty much as fast as he wants. Heading north between blurring swaths of pastureland, he slows and points out some wheat, expecting to point out nothing really, as he had done in another dismal-looking section. But he’s surprised at how green these clumps are, and for a moment, at least, his good-natured facetiousness about the sad condition of his crops turns into some sort of satisfaction.

“I’m pretty pleased,” he says, speeding up again to check on some cattle elsewhere.

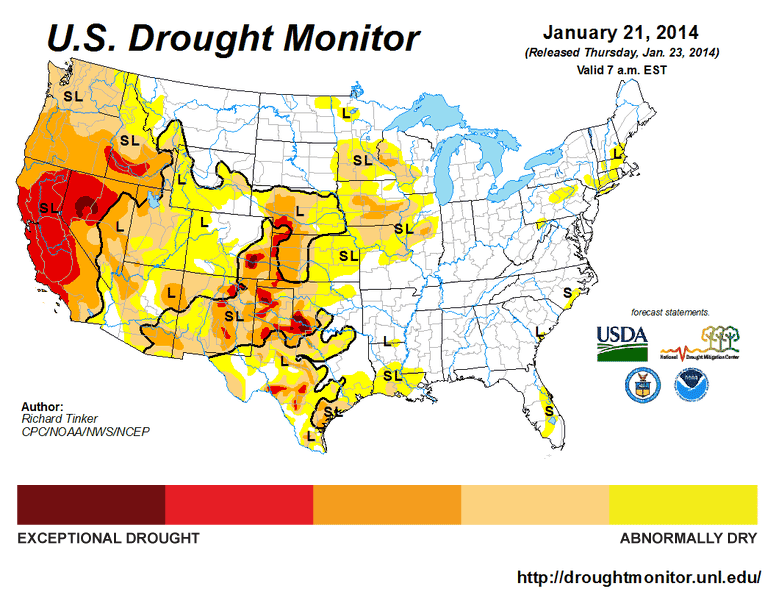

The Panhandle is a vast region, and its weather can vary dramatically. Even average annual rainfall totals can shift by several inches within a couple hours’ drive. Where Perrin is positioned, the average yearly rainfall historically is 20 inches. As of late February, he’d not seen not one inch of it, and the fact that rains generally don’t fall in these parts until April wasn’t much comfort.

After all, meteorologists aren’t exactly keen on the chances for recovery this year.

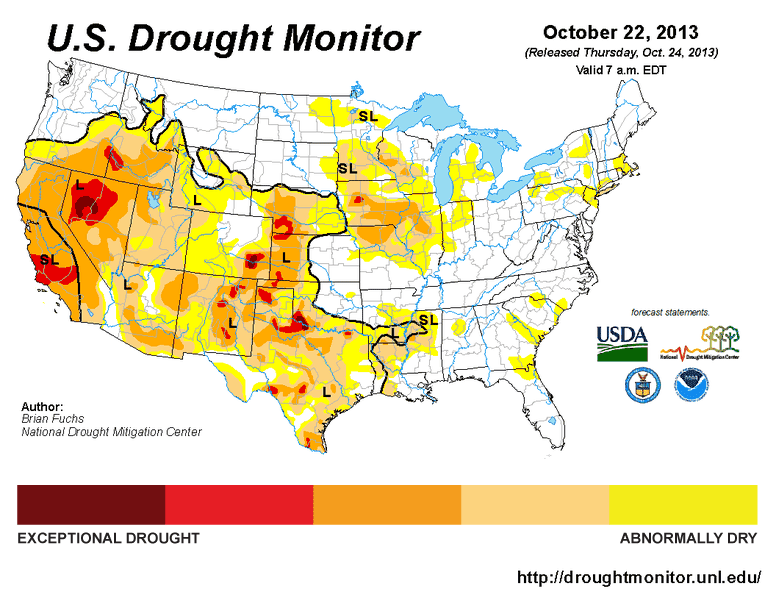

“If we get a year in Texas where the entire state is well above normal and gets timely rains for forage, you’ll see a good rebound,” says Brian Fuchs, a climatologist with the National Drought Mitigation Center at the School of Natural Resources, University of Nebraska-Lincoln. “But another dry year could put them back to 2011. They’re in a very vulnerable state.”

John Perrin, on his 8,000-acre ranch in Deaf Smith County, Texas, in late February, was forced to pen his cattle and bring feed to them on his parched land. If there had been pasture, they’d have been free to roam and graze. Photo credit: Tom Johnston

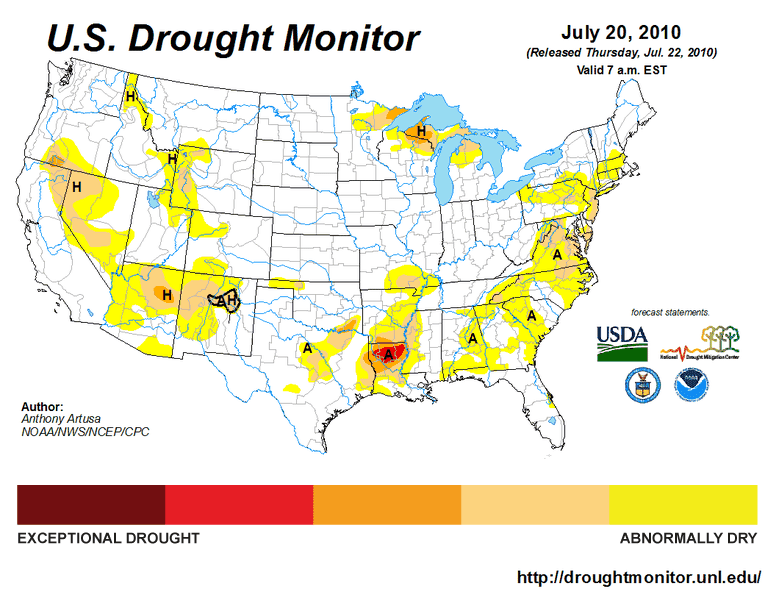

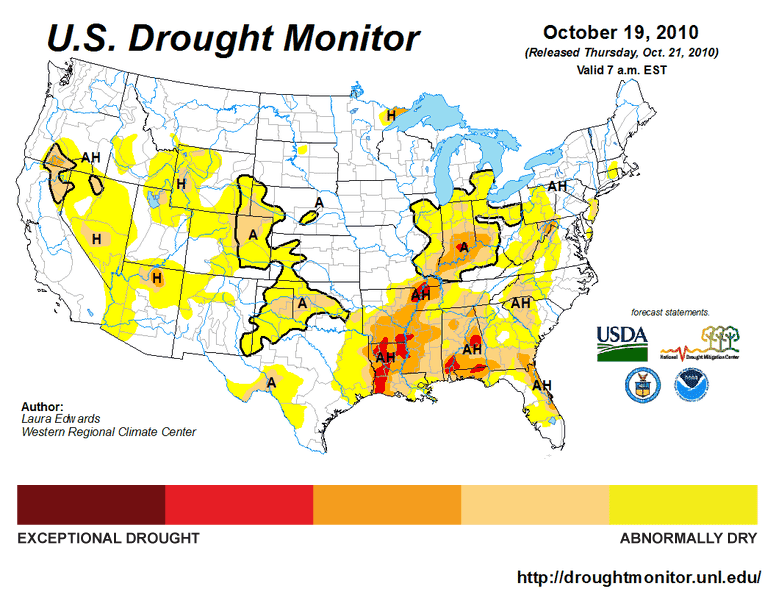

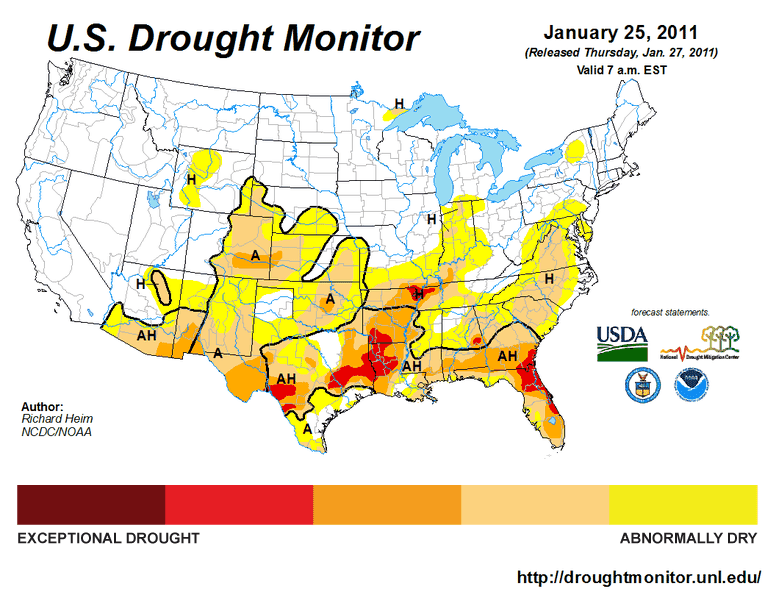

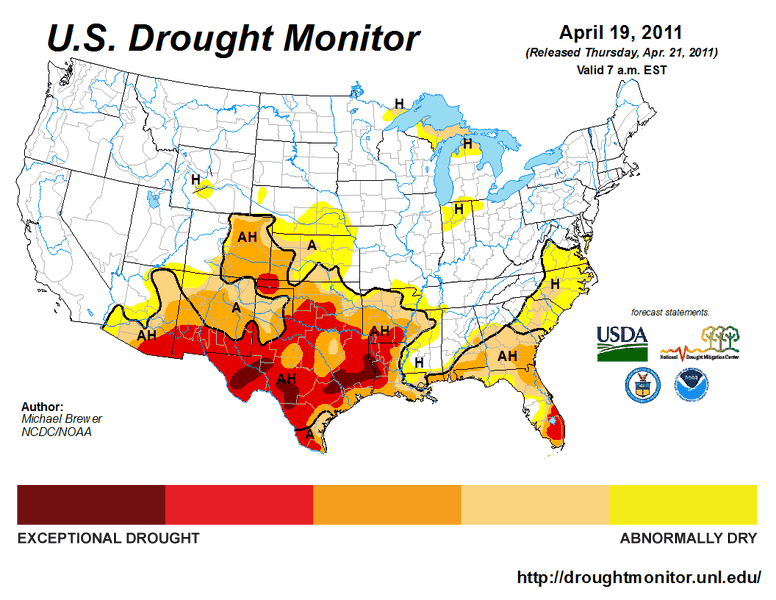

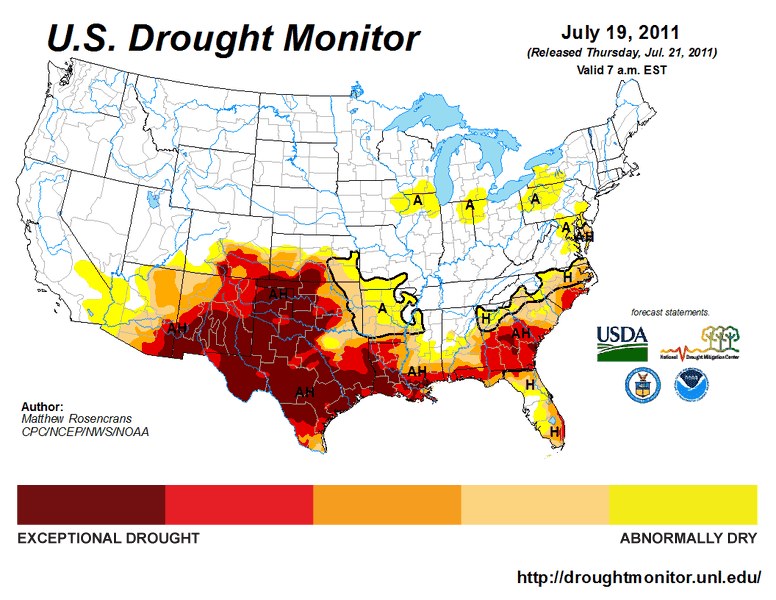

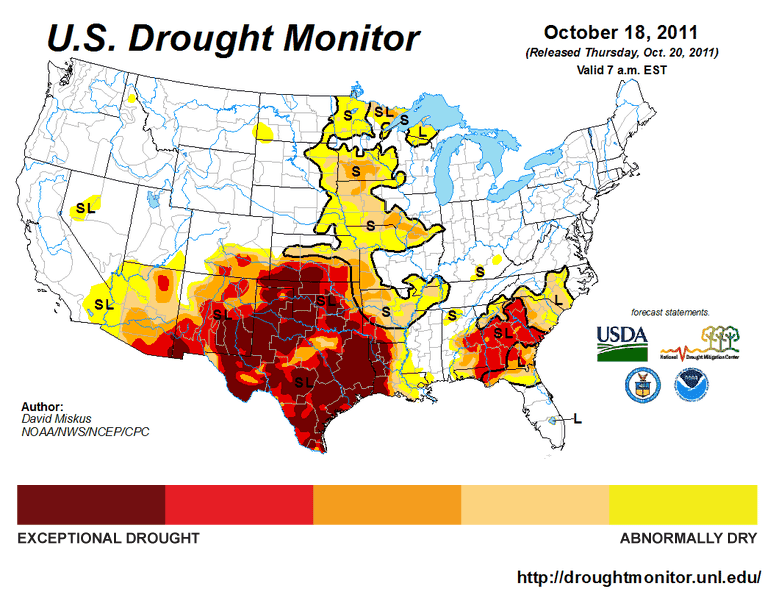

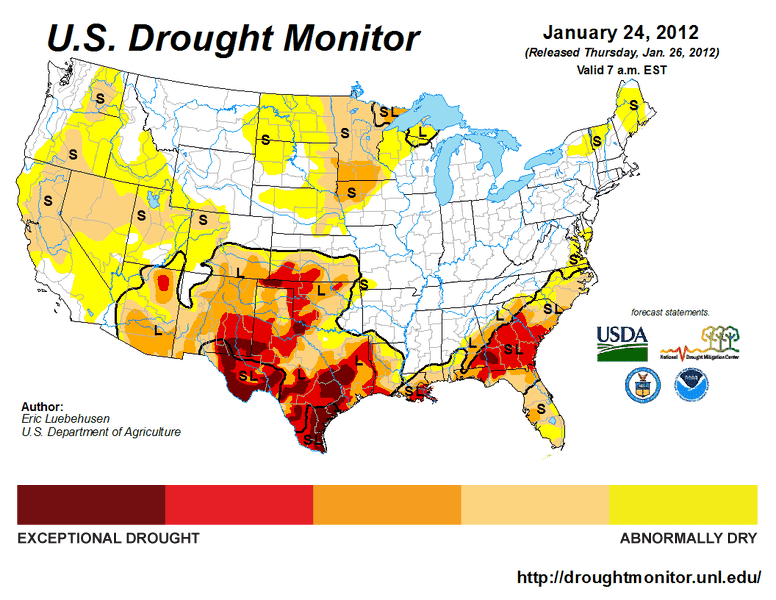

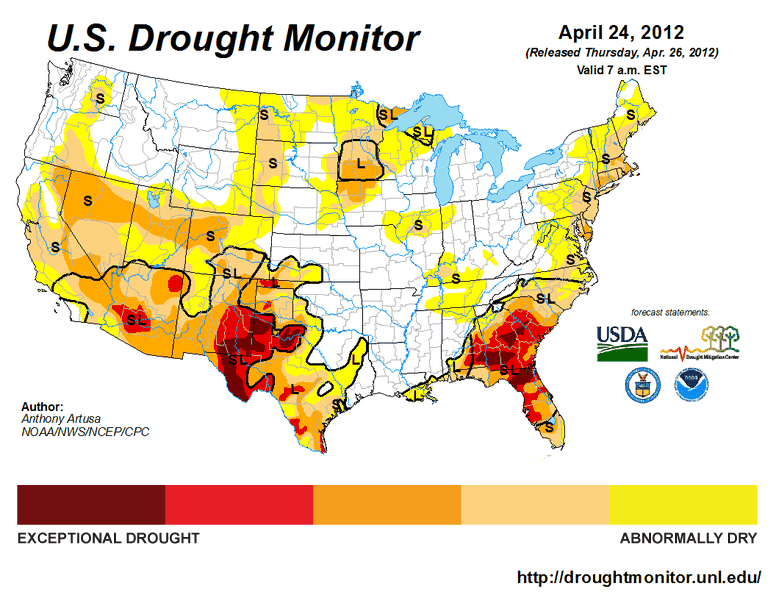

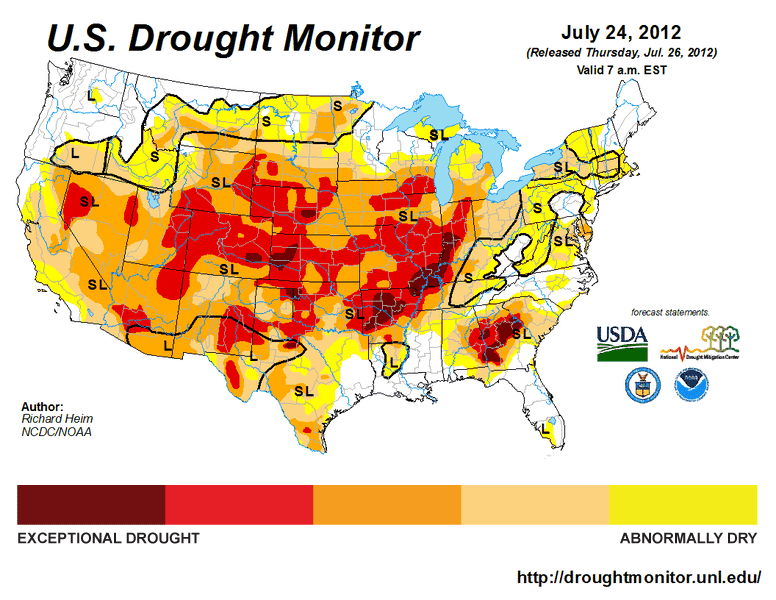

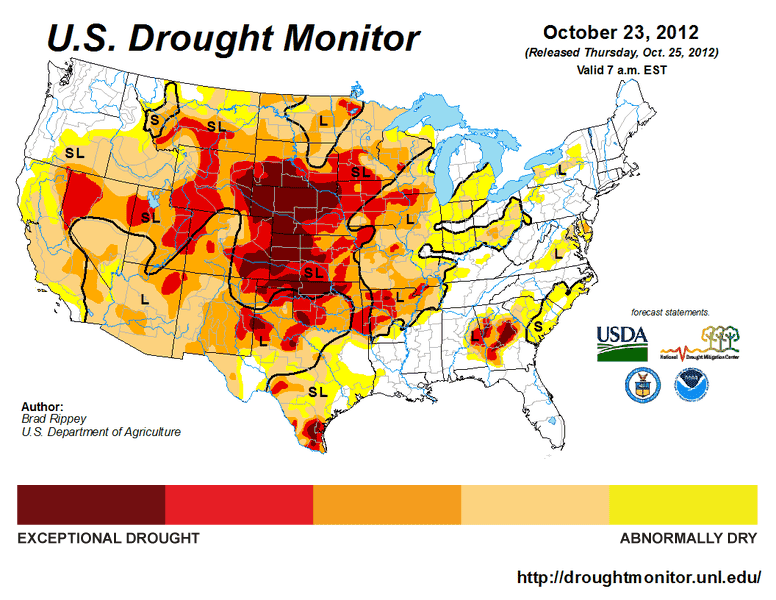

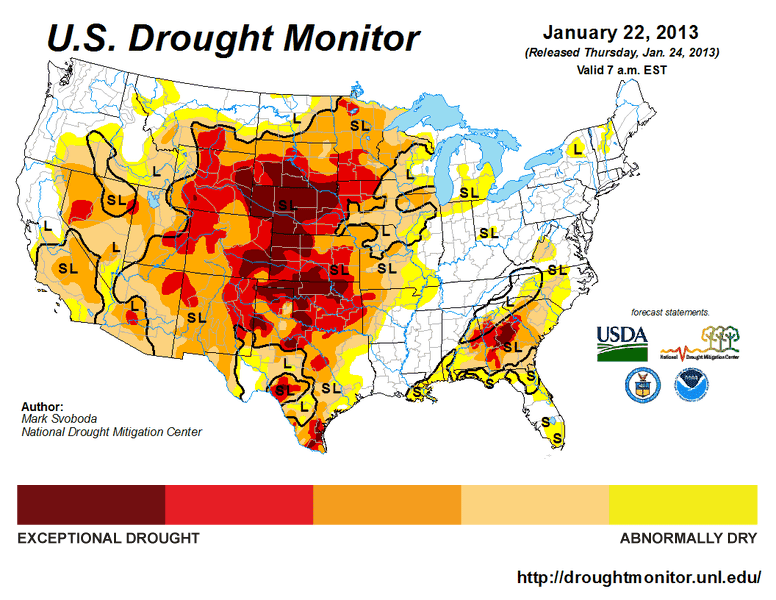

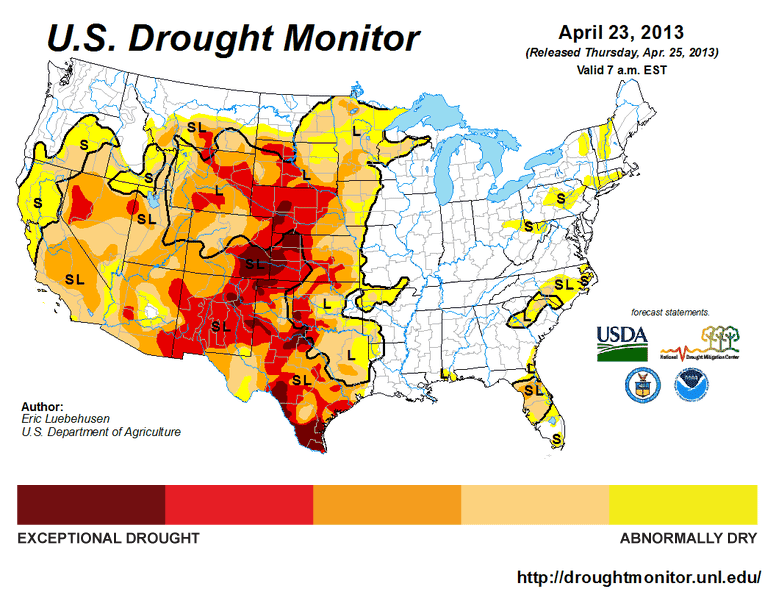

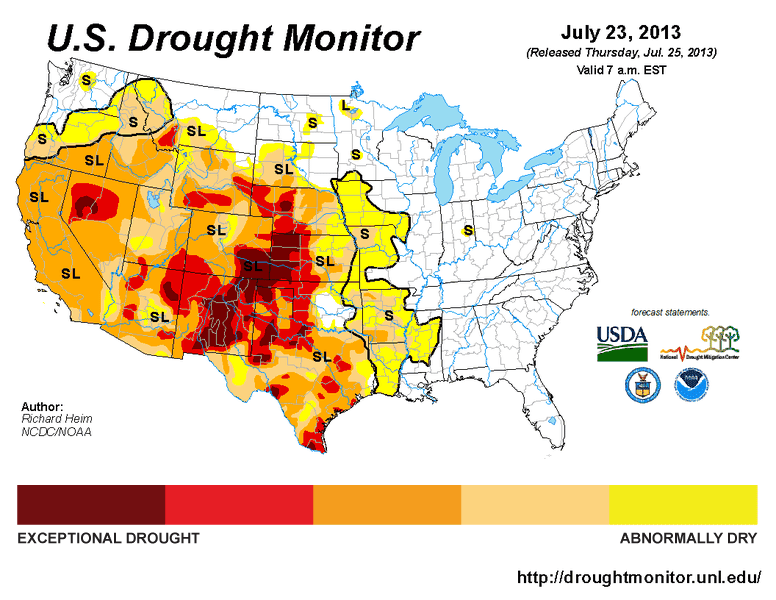

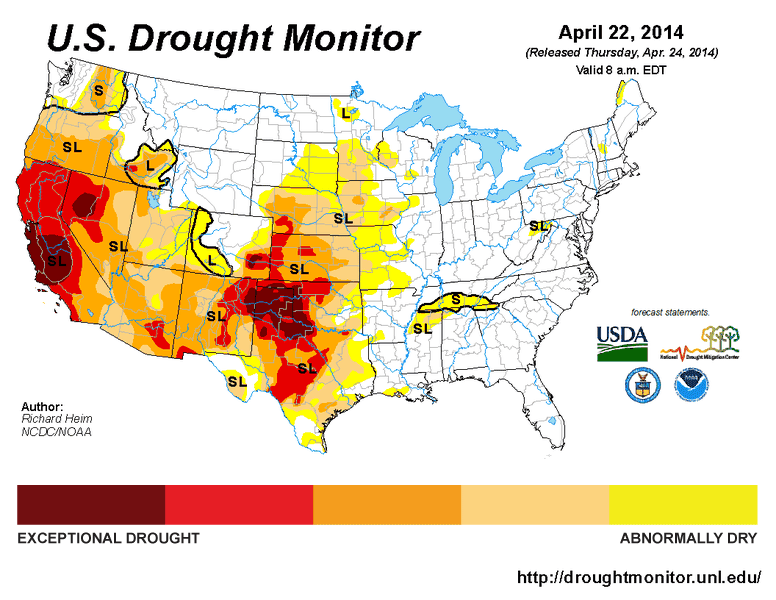

It’s not looking so good for 2014. Rains finally began in earnest in May and through July 29 amounted to 10.46 inches in Lubbock, Texas, according to the federal Drought Monitor. The precipitation deficit, however, was 30.47 inches accumulated from January 2011 to April 2014, and the long-term impact still is showing in limited lake levels and subsoil moisture. On July 27, USDA reported that subsoil moisture was rated 65 percent very short to short in both Oklahoma and Texas. Rangeland and pastures, meanwhile, had some improvement and were rated just 24 percent very poor to poor in Texas, along with 20 percent in Kansas and 19 percent in Oklahoma.

Texas’s own chief climatologist even has predicted dry conditions stretching all the way to 2020.

Such forecasts are raining on the producers’ parade.

“I would expand (my herd) back too,” Perrin says, “if I had the rains. The Panhandle region, pretty much all the square part of it, is pretty deficit in rainfall, and I don’t think hardly any cow expansion will be happening here. The rest of the state has come out quite a bit better and had some rains, and if they continue to have some rains I think there’ll be some herd rebuilding there.”

Hot spots

It must be frustrating; producers can’t see rain in the future when the market is baring bull’s horns so clearly now, with record prices throughout the live-animal-to-retail meat continuum. Cattle futures reached a record $1.47 per pound on March 5 on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange, a 25 percent jump from the 2013 low a year earlier, and retail prices remain sky-high, as well.

“We all want to restock, and I’m as guilty as the next guy in wanting to rebuild the herd,” says Jay O’Brien of Amarillo-based Corsino Cattle Co./JA Ranch.

Some of O’Brien’s land in West Texas has seen more recovery than has Perrin’s. While the rancher in him intends to do his part in helping Texas rebuild its herd, his experience in 2011 tempers some of the cowboy braggadocio. He had to send half his stock — the 1-year-olds (yearlings) — to feed yards at a discount. Looking back, he admits he was overstocked. But then, 2010 had been a good year.

You can’t exactly predict a drought, and you surely can’t forecast its nature. The 2011 iteration was particularly mean, with temperatures exceeding 100 degrees F on more than 100 days of the year.

We’re like those people in ‘East of Eden.’ We think we’re in healing mode. It’s probably foolish of us, but we’re optimists so we’re acting that way.

So survival for O’Brien and his brethren requires a strategy that allows flexibility. He constitutes his herd with half yearlings and half cows so that he can liquidate in a hurry if necessary. The priority goes to keeping the cows, especially because they’re going for some $2,000 a head nowadays, more than double the $800 or so they fetched in 2011. He had the option this past fall of expanding the cowherd, and the economics screamed for it, but that would surrender the flexibility. If the shoe were to drop again, he’d have to merchandise those precious cows.

“We’re like those people in ‘East of Eden,’” O’Brien says, referring to the John Steinbeck classic. “We think we’re in healing mode. It’s probably foolish of us, but we’re optimists so we’re acting that way.”

Optimism

Optimism is evident in USDA data showing that replacement heifers held as a percentage of beef cows in January was 18.8 percent nationally. As Kansas State University ag economist Glynn Tonsor notes, that’s higher than the peaks in past efforts to expand. “That said, holding back heifers only to have ongoing cow culling has limited ability to gain traction in aggregate expansion,” he says.

West Texas rancher John Perrin explains the tough decisions he must make during severe drought conditions.

Perrin readily admits he’s thought about giving it all up. But it’s just a thought. The reality here is, when the going gets tough, the tough adapt — as evidenced by the cows he’s penned in a sort of makeshift feed yard in the middle of nowhere. They’d normally be roaming and grazing his pastureland.

“I’m keeping heifers, and if I had rain I’d be breeding them and increasing my herd with them,” he says. “Since I’m not going to have pasture to breed them, I’ll probably just sell all these as open heifers, and hopefully get a premium by selling them as breeding stock in this market that’s pretty hot.”

Regardless of what happens weather-wise, we’re headed toward the next drought.

Much the same for Rick Kellison, a rancher just east of Plainview, Texas, who was forced to sell off 60 percent of his herd as a result of the drought. He also plans to hold on to his top-end heifers as long as he can and, should he have to, take them to a rainier area of the state and sell them as bred heifers. He’s aiming for quality, not quantity. He also has a goal to always have two years of good hay in storage.

“Our plan is to never go back to the same number of cows that we had prior to the drought. Part of that is we were overstocked,” Kellison says. “Regardless of what happens weather-wise, we’re headed toward the next drought.”

In the next chapter, we will explore what that means for the part of the industry that turns the live animal into beef. The Packers